Guest Blog: Joe Milnes

Smiley Joe

The next in our series of guest blogs is from Joe Milnes. Joe joined our training in Dover once we were able to start this year. There were a couple of things that I will never forget about Joe’s training:

He’s always smiling. I mean ALWAYS smiling. He smiles before training, during feeds and afterwards.

He developed a fantastic hat line - it definitely won the hat line of the year. It then seemed to fade a bit for the next week, only to come back with vengeance again!

Joe’s work ethic was impeccable. I think he’d have kept on knocking out the big swims if we’d not suggested it was time to taper.

Anyway, enough from me. You get it, I’m a Joe fan. Over to Joe to talk about his journey in his words.

Six weeks to swim the channel

Something that is always said of the Dover Channel Training (DCT) community is what a friendly, unique and inclusive group it is. The most eclectic bunch of people you can imagine, all united by the ridiculous goal of setting off from a beach in Dover and swimming day and night until they stand up on a beach in France…..The reward for all those months of preparation, the (not insignificant) cost and the physical and mental hardship?? A pebble. In such a bizarre set of extreme circumstances the camaraderie that you regularly witness amongst DCT members makes sense. Throughout my weeks at DCT there was one characteristic of the group, however, that I just couldn't get my head around. The unsuccessful swims seemed to be celebrated with as much enthusiasm and excitement as the successful ones! It's not a *pat on the back* 'ah, well nevermind' that you might get from friends if you pulled up halfway through a 10k, but genuine and sustained congratulations on the achievement. It just didn't make sense to me….. until I completed my swim just over a week ago. I learned a lot over the course of the swim last week - the first three lessons I would say are essential for any prospective channel swimmer. The last lesson, ‘The Pebble’, has changed my outlook on success forever.

Like many swimmers this year with early slots booked (my original tide was the beginning of June) I'd quickly come to the realisation during lockdown that my swim would be postponed until 2021. I was disappointed, as training had been going well, and although I hadn't done any long swims, I felt strong in the water and had been looking forward to seeing how my body adapted to the longer training swims. With the pressure off, and access to pools restricted, I spent lockdown trying to maintain an element of fitness, going for the odd run and taking part in YouTube circuit training sessions, safe in the knowledge I'd have plenty of time to ramp up my swim training through the winter and into the summer of 2021. You can imagine my delight, then, when Eddie, my pilot, emailed me in the middle of July to say he'd got a slot in the next few days if I was ready. 'If I'm ready' I was thinking? No! Steady, Eddie, I'm pretty bloody far from being ready'. Three sessions of Joe Wicks' YouTube circuits, a one-off 4k in the Thames and 3 dips in the Serpentine lido wouldn't really cut it for the biggest physical and mental challenge of my life. I politely declined the offer of a slot in 6 days time, but stated that if Eddie thought he could fit me in from September onwards, then I'd commit to be as ready as I could be - 'get your skates on, Joe, we'll fit you in, no problem'. I could start training with DCT for my first long swim on the 1st August, which would give 6 weeks to ramp up and taper back down before a possible slot in the second week of September. It didn't seem like a lot of time. Was I being hopelessly optimistic?? Only time would tell.

Channel lesson 1: Become comfortable being uncomfortable

I can't remember when or where I first heard about the idea of becoming comfortable being uncomfortable, but an understanding of this concept meant that when faced with only 6 weeks to prepare for the swim, I’d start my swim confident in my physical ability to complete it.

The concept is based on a theory that fatigue during performance is a psychological state, as opposed to a physical condition. Think of a car driving at 30mph in first gear. For those not aware that the car has 4 more gears, the car would sound like it was screaming for the driver to stop accelerating. However, those familiar with the gearing system would be more than aware that the car has more gears to slip into and the screaming sounds from the engine are being perceived incorrectly. The engine has much more to give!

I wanted to tap in to this theory, and the practice grounds became the Sunday sessions on my 'back to back' DCT training weekends. My arms, shoulders and back would be crying out for rest after the long Saturday swims, but I would drive down to Dover on the Sunday morning, telling myself that the training session would be a great opportunity to practice ‘becoming comfortable being uncomfortable’. I swam with the sole aim of changing how I perceived the discomfort in my limbs. I'm convinced that these sessions were the most important I attended. Not because of the additional training volume, but because I was able to develop the ability to experience fatigue in a different way. Yes, the channel hurt physically, but it was always going to hurt. At no point did I perceive the pain or discomfort as a degradation of performance or in my ability to complete the swim. I had a rough patch at about five hours when my body switched to burning fat from glycogen, but the physical pain didn't become unmanageable at any point after that and I have no doubt this was due to an altered perception for how the body can perform when 'fatigued'.

Channel lesson 2: Swimming from feed to feed.

'Just swim from feed to feed' are instructions that any DCT swimmer will have ringing in their ears for weeks prior to the swim. I would re-emphasise the words of all the DCT crew and say that this lesson is an absolute essential!

Each time I came in for a feed, on the hour every hour, I'd enjoy chatting to Aaron and Jess, my support crew. It was an opportunity to reset, to focus on a goal for the next hour or something to look forward to, and crack on.

It's amazing how you can pass an hour. I spent an hour looking forward to Jess joining me for the support swim, I spent an hour enjoying the sunrise, I spent an hour looking forward to my UCAN mocha (recipe in the appendix), I even spent an hour trying to call dolphins (a skill I'd convinced myself prior to the swim that I might possess, although sadly this didn't pan out on the day).

For the time I kept control of my thoughts, and concentrated on swimming to the next feed, I was able to largely enjoy the experience of swimming without worrying about the endless kilometers remaining.

Channel lesson 3: Controlling the controllables

The only thing that all channel crossings have in common are a boat, an observer and a whole lot of swimming! It is a sea of variables! Greek stoics were the first to write about a key to success being keeping control of things that you can control, and not wasting physical or emotional energy on the things you can’t. This thought process should be one adopted by every prospective channel swimmer!

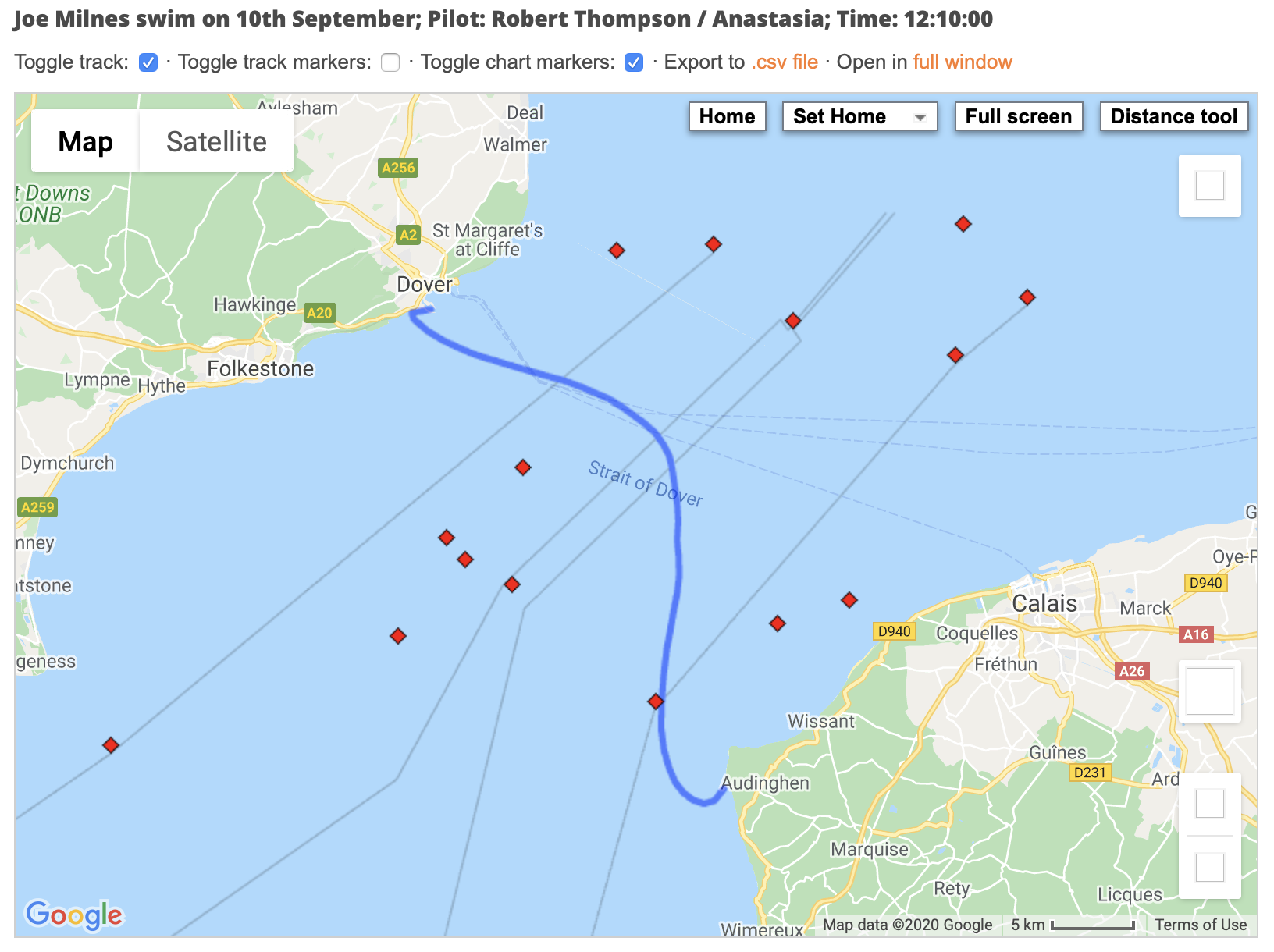

Prior to the big day we have ample opportunities to influence controllables - training, nutrition, equipment, crew recruitment etc. all of which will contribute to the success, or otherwise, of the day. On the big day, however, your responsibilities start and end with swimming. For 11 out of the 12 hours and 10 minutes I was swimming last week, I can reflect and be hugely satisfied with how I handled the day - mentally and physically - however, around ten and a half hours into my swim I neglected to focus on controlling the controllables, and so began a complete mental unravelling, to the point I'd almost convinced myself that my swim was about to end and I was being pushed back out to sea!

This unravelling wasn't brought about by any significant event, rather a subconscious decision to start worrying about small things I couldn't control. I made a number of small mental mistakes which escalated and reverberated around my fatigued head to the point I'd whipped up a storm of negativity which threatened to completely ruin the day.

Around 10 hours into the swim I saw how close France was, and asked my support crew to let me know how many feeds I'd likely have left (something I’d said that I wouldn’t’ do)… I then started to focus on what time I might do...and when I looked at France again, and could see she wasn't getting any closer, I started to panic! What was going on? Was something wrong? Had the tide turned? Had I missed the landing spot? Was I getting washed out? It was in the midst of this unravelling that one of the crew noticed my procrastination and took matters into their own hands by coming out onto the deck and saying in the most stern and direct way possible 'Joe, you need to swim. NOW'.

It was all I needed, a jolt back to reality and a reminder that my responsibilities started and ended with putting one arm in front of the other. I did what I should have done an hour previous and started to swim hard, with my head down. A few minutes later I saw the motorised dinghy being lowered from the boat, which I knew was a sign that we were approaching the shallows. I then noticed a change in water temperature and the taste of seaweed in the water, before I saw rocks and sand beneath me, tempting me to try and stand up. A few strokes more and I was able to clamber up on to the beach and pull myself clear of the water. I was over the moon. Elated, yes. But the overall feeling was relief. Letting my thoughts get the better of me for those final few kilometers before France had taught me a brutal but effective lesson in the importance of focussing on controlling the controllables.

Channel lesson 4: ‘The Pebble’.

So going back to the beginning of this blog. What was I missing when I first travelled down to Dover? Why couldn’t I understand the celebration and encouragement awarded to unsuccessful attempts? It wasn’t until I was travelling back to England on the boat, staring at the pebble I’d just collected from the beach in France, that it suddenly became crystal clear.

Yes, I was a channel swimmer, and yes, I had my pebble, but looking back, the most important lessons for that day had happened before I got to France. If I’d have been pulled out of the water 200m from France the lessons would have been exactly the same. All I got by getting to France was that pebble.

The pebble isn't why any of us attempt this. Of course it isn't. The reward is in the experience. It’s found within the sacrifice, hours of preparation and hardship you put yourself through to get there. The pebble is a reminder, that when we truly commit to something we want to achieve, the process of getting better trumps any extrinsic reward or recognition that we could get upon completion of the task.

Some of the most successful channel swims will not be found within Julian Critchlow's spreadsheet. Some of the most amazing feats of channel swimming endurance cannot be searched on the CSA or CSPF websites. Success is found in pushing limits and finding them, even if they're found 300 meters from France.

It's an appreciation and complete understanding of this which makes this eclectic group of people at Dover so special, and why I’m grateful to have experienced a small part of this magic. I have no doubt that I will carry this experience and these lessons with me to whatever challenges I face next.

What else would we do for a pebble??

Acknowledgements:

‘Controlling the controllables’ and ‘Being comfortable being uncomfortable’ are concepts that crop up in various different sources, both appear in this context in ‘The Art of Resilience’ by Ross Edgley - a fantastic read for anyone interested in ultra endurance.